- Home

- Gordon-Reed, Annette

The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family

The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family Read online

THE HEMINGSES of MONTICELLO

ALSO BY ANNETTE GORDON-REED

Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy

Vernon Can Read!: A Memoir (with Vernon E. Jordan, Jr.)

Race on Trial: Law and Justice in American History (editor)

THE HEMINGSES of MONTICELLO

AN AMERICAN FAMILY

ANNETTE GORDON-REED

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

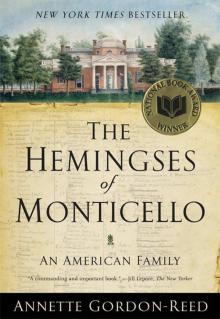

Frontispiece: Watercolor of Monticello. (Courtesy of Massachusetts Historical Society)

Copyright © 2008 by Annette Gordon-Reed

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Production manager: Andrew Marasia

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gordon-Reed, Annette.

The Hemingses of Monticello: an American family / Annette Gordon-Reed.—1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-0-393-07003-3

1. Hemings family. 2. Hemings, Sally—Family. 3. Jefferson, Thomas,—1743–1826—Family. 4. Monticello (Va.)—Biography. 5. Albemarle County (Va.)—Biography. 6. Slaves—Virginia—Albemarle County—Biography. 7. African American families—Virginia—Albemarle County. 8. African American families. 9. African Americans—Biography. 10. Racially mixed people—United States—Biography. I. Ttile.

E332.74.G67 2008

973.4'60922—dc22

[B]

2008014642

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

TO MY HUSBAND, ROBERT REED, AND OUR DAUGHTER, SUSAN JEAN

GORDON REED, AND OUR SON, GORDON PENN REED

CONTENTS

Chronology of the Hemings Family

Preface

INTRODUCTION

PART I

ORIGINS

1 YOUNG ELIZABETH’S WORLD

2 JOHN WAYLES: THE IMMIGRANT

3 THE CHILDREN OF NO ONE

4 THOMAS JEFFERSON

5 THE FIRST MONTICELLO

6 IN THE HOME OF A REVOLUTIONARY

PART II

THE VAUNTED SCENE OF EUROPE

7 “A PARTICULAR PURPOSE”

8 JAMES HEMINGS: THE PROVINCIAL ABROAD

9 “ISABEL OR SALLY WILL COME”

10 DR. SUTTON

11 THE RHYTHMS OF THE CITY

12 THE EVE OF REVOLUTION

13 “DURING THAT TIME”

14 SARAH HEMINGS: THE FATHERLESS GIRL IN A PATRIARCHAL SOCIETY

15 THE TEENAGERS AND THE WOMAN

16 “HIS PROMISES, ON WHICH SHE IMPLICITLY RELIED”

17 “THE TREATY” AND “DID THEY LOVE EACH OTHER?”

18 THE RETURN

PART III

ON THE MOUNTAIN

19 HELLO AND GOODBYE

20 EQUILIBRIUM

21 THE BROTHERS

22 PHILADELPHIA

23 EXODUS

24 THE SECOND MONTICELLO

25 INTO THE FUTURE, ECHOES FROM THE PAST

26 THE OCEAN OF LIFE

27 THE PUBLIC WORLD AND THE PRIVATE DOMAIN

28 “MEASURABLY HAPPY”: THE CHILDREN OF THOMAS JEFFERSON AND SALLY HEMINGS

29 RETIREMENT FOR ONE, NOT FOR ALL

30 ENDINGS AND BEGINNINGS

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Notes

Selected Bibliography

CHRONOLOGY OF THE HEMINGS FAMILY

1735

Elizabeth Hemings (EH) is born.

1746

The marriage of John Wayles (JW) and Martha Eppes brings EH to the Forest.

1748

Martha Wayles is born. Martha Eppes dies and leaves EH as JW's property.

1753-61

EH gives birth to Mary and Martin Hemings, Betty Brown, and Nancy Hemings.

1762-70

EH gives birth to five children by JW: Robert, James (JH), Thenia, Critta, and Peter.

1772

Martha Wayles Skelton (MWJ) marries Thomas Jefferson (TJ), and Betty Brown comes to Monticello as MWJ's maid.

1773

John Wayles dies at the Forest. The Hemingses come under the ownership of TJ and (MWJ). Sarah (Sally) Hemings (SH), the last child of EH and JW, is born.

1774

The Hemings family moves to Monticello

1776-77

TJ in Philadelphia drafts the Declaration of Independence; fourteen-year-old Robert Hemings (RH) lives with him as a manservant. John Hemings, last son of EH, is born at Monticello; in 1777 her last child, Lucy, is born.

1780

Joseph Fossett, son of Mary Hemings, is born.

1781

Wormley Hughes, son of Betty Brown, is born.

1782

Martin Hemings is left in charge of Monticello when TJ escapes from Tarleton's troops.

1782

MWJ dies at Monticello.

1783

SH goes to Eppington with TJ's daughters. Burwell Colbert, son of Betty Brown, is born.

1784

RH trains as a barber. JH goes to France with TJ.

1787

SH travels to London and lives with Abigail Adams, then joins her brother JH in Paris. Mary Hemings is leased to Thomas Bell.

1789

When SH balks at returning to America, TJ promises her a good life and the freedom of their children when they become adults. JH and SH return to Monticello in December.

1790

JH and RH go to New York with TJ. SH gives birth to her first child, who dies.

1791

JH goes to Philadelphia to serve as chef de cuisine in TJ's home.

1792

Mary Hemings asks to be sold to Thomas Bell. Martin Hemings asks to be sold to anyone.

1793

TJ puts his agreement to free JH in writing.

1794

TJ draws up a deed emancipating RH.

1795

TJ files the RH deed, and RH becomes legally free. Harriet Hemings I, daughter of SH and TJ, is born at Monticello.

1796

TJ draws up a deed emancipating JH. JH goes to Philadelphia, TJ files the deed, and JH becomes legally free.

1797

Harriet Hemings I dies.

1798

William Beverley Hemings, son of SH and TJ, is born.

1799

The first published allusions to TJ and SH appear in the press.

1800-01

Mary Hemings and her children Robert Washington Bell and Sarah Jefferson Bell inherit Thomas Bell's property upon his death. Harriet Hemings II is born at Monticello. JH turns down TJ's request that he become chef in the President's House. JH commits suicide in Baltimore.

1802

James Callender exposes the relationship between SH and TJ.

1805

James Madison Hemings, second son of SH and TJ, is born. Beverley Hemings is identified as the eldest son of TJ and SH.

1807

EH dies at Monticello. Joseph Fossett takes charge of the blacksmith shop at Monticello.

1808

Thomas Eston Hemings, the last child SH and TJ, is born at Monticello.

1809

TJ retires from public life. Burwell Colbert becomes his principal manservant and butler. John Hemings takes charge of the Monticello joinery.

1

810-26

Beverley and Madison and, then, Madison and Eston Hemings serve as apprentices to their uncle John Hemings, at Monticello and Poplar Forest. Harriet Hemings learns to weave.

1822

Beverley and Harriet leave Monticello to live as white people.

1826

TJ drafts a will formally freeing Burwell Colbert, Joseph Fossett, John Hemings, and Madison and Eston Hemings. TJ dies. SH, Madison, and Eston Hemings move to Charlottesville.

1827

The auction at Monticello disposes of TJ's personal property; the Hemings family is dispersed.

1831

Monticello is sold.

So the beginning of this was a woman...

—ZORA NEALE HURSTON,

Their Eyes Were Watching God

PREFACE

A NUMBER OF YEARS back, while at the Massachusetts Historical Society for a speaking engagement, I had the chance to read through the original version of Thomas Jefferson’s Farm Book, an extremely valuable part of the society’s collection, a pivotal document within the vast array of the written material that Jefferson produced over the course of his very long lifetime. In it he recorded the names, births, family configurations, rations, and work assignments of all the people enslaved on his plantations. Waiting for books in research libraries was nothing new to me, but this time the anticipation was almost exponentially heightened because I was finally going to get to see and touch an item that I had been reading in facsimile form since high school. The librarian brought the Farm Book out to me, and I was slightly startled by its size. It was much smaller than I had imagined it would be and much more well-preserved, and I knew the society was taking great pains to keep it that way. The librarian left me alone. When I opened the pages to see that very familiar hand and the neatly written entries, many of which I knew by heart, I was completely overwhelmed. For a time I simply could not continue.

There had been other moments before then when I was brought up short while reading through the Farm Book and thinking of the people described in it and of the man who wrote it: Just who do you think you are!? He determined who got fish, and how many; who got cloth, and how much; and the number of blankets that were given out—the course of the lives of grown men, women, and their children set by this one man. I knew everything that was in the book, and understood what it meant long before I sat down to look at it again that day. Still, it was wrenching to hold the original and to know that Jefferson’s actual hand had dipped into the inkwell and touched these pages to create what was to me a record of human oppression. It took my breath away.

Of course, Jefferson did not see the Farm Book as I did. Had he thought it merely a record of oppression (greatly as he craved posterity’s favorable judgment), he would never have kept it. Certainly members of his legal white family would not have preserved it. They, too, were anxious to safeguard and cultivate his legacy because they loved him deeply and because their own sense of self was so firmly tied to that legacy. It is, in fact, highly unlikely that it ever occurred to Jefferson that his record of the lives of his slaves would become the subject of scholarly interest, even a passion among some—that his slaves’ lives would be chronicled and followed in minute detail, the interest in them often unmoored from any interest in him. No, this was a workaday document to tell him what he had to buy from year to year, to keep some sense of what would be needed to continue operations. In Jefferson’s monumentally patriarchal and self-absorbed view, one shared by his fellow slave-owning planters, this was Oh, the responsibilities I have! Here is what I have done and have yet to do for all “my family.”

The word “family” brings us to the subject of this book: the Hemingses of Monticello. No one can know what they, who were his family both biologically and in the figurative sense in which Jefferson meant it, thought about the Farm Book. They are listed there too—his wife’s sisters and brothers, their children, their mother, and his own children. Members of the family almost certainly knew it existed, and if they knew, their other relatives knew as well. Martin, Robert, James, and Sally Hemings—their nephew Burwell Colbert—among others, were close enough to Jefferson to see his books, to come upon him working, to know the important and not so important things, emotional and physical, that were in his life.

However familiar they were with its contents, one thing that all of the enslaved people at Monticello would have known about the Farm Book, not just the Hemingses, is that it described some parts of their lives, but definitely not all, reproducing only a tiny fraction of a snapshot of life at Monticello that provides a very useful baseline for inquiry. What is in the book must be added to information from other sources, including the statements and actions of the Hemings family, Jefferson’s family letters, even some writings from Hemingses that reveal the family’s complicated relationship to the master of Monticello, and the wealth of information about the institution of slavery as it was lived during the Hemingses’ time.

That the names of the children of Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson appear in a book detailing the lives of slaves conveniently and poignantly encapsulates the tortured history of slavery and race in America. But Monticello was a world unto itself for four generations of Hemingses whose lives cannot be reduced to the saga of one nuclear family within its bloodline, important as that subset was. We must, and will, pay attention to them, but they were only part of a much larger family story. Opening the world of the other members of this family—to see how those particular African Americans made their way through slavery in America—is the purpose of this book. Theirs was a world that is (mercifully) gone, but must never be forgotten.

THE HEMINGSES of MONTICELLO

INTRODUCTION

IN SEPTEMBER OF 1998, the Omohundro Institute of Early American Culture and History and the College of William and Mary, in Williamsburg, Virginia, hosted a conference designed to give scholars of slavery a preview of a newly compiled database of transatlantic slave voyages. For the first time in history, records of every known voyage of slave-trading vessels operating between Africa and the Americas would be available in a CD-ROM format. The implications for scholarly research were staggering. Information about an activity central to the development of the modern Western world would be available at the touch of a finger.

Though the conference unveiling this new research tool was designed primarily for scholars, with a heavy tilt toward those interested in economic history, scores of laypeople—mainly blacks—came too, hoping to find some word, some trace, of their ancestors. Not all were looking for “ancestors” in the general sense in which many blacks refer to those enslaved in America from the seventeenth century through most of the nineteenth. It was clear that many hoped the database might help them find their specific progenitors—what their names were and where they came from. Others not interested in their own genealogy apparently had come hoping to hear more of the lives of individuals who endured the Middle Passage.

Their hopes were largely dashed. There were no passenger manifests for slave voyages. Slavers were not interested in the names of the Africans bound for bondage in the New World. Notations about the voyages served strictly business purposes and included the names of the vessel, the captain, and, perhaps, a first mate, the number of the human cargo, where they came from, and where they were going, along with any onboard events that might inform future voyages. Was there a revolt, a problem with rations? It was left to the enslaved Africans to keep the memory of their identities and origins alive—no small task, particularly in the land that would become the United States, as generations passed and Africans became Americans.

While the conference was just about what I had expected, it frustrated many of those who had come to Williamsburg hoping to make a personal connection to the African captives. Each day when we broke for lunch or refreshments, I could hear murmurs of concern about the way things were proceeding. By the end of the conference, one participant, angered by what he perceived as the coldness of historians talking about slavery in te

rms of “the numbers of people sent here” and “the numbers of people sent there,” erupted. The conference, he charged, was devoid of feeling and emotion. Where was the scope of the human loss? Where was the sense of the bottomless tragedy of it all?

Of course, the evidence of human loss and tragedy was right there. The numbers told a story, but in the detached and steely way that numbers tend to do. Slavery had many aspects, and getting a handle on the logistics and economics of the institution (how many people were moved, how many ships were used, how many miles over the ocean were covered, how much money was made) is as vital as telling personal stories—as vital but, perhaps, not as immediately compelling. It is a safe bet that most people respond more forcefully and intensely to other people than to numbers. So the lament about the conference’s alleged focus on numbers compiled to suit the aims of businessmen, if not a little unfair, was understandable. Statistical data about a cargo of human beings, deplorable and heartrending as that is, is depersonalized. One yearns to know the individuals behind the statistics. What were their names? There is great power in a name. What were their lives like before the horror that engulfed them? How did they cope in the New World? What were their stories?

The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family

The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family